Explainer last updated May 14, 2020

Chapter 3 of the FARC-government peace accord (“End of the Conflict”) laid out a plan for the disarmament, demobilization, and eventual reintegration of the FARC’s membership. It established a ceasefire and a detailed timetable for laying down of arms, with monitoring and verification carried out by a United Nations mission. It then laid out procedures, benefits, and responsibilities for ex-combatants’ re-entry into Colombian society.

In the months after December 1, 2016, the day the Colombian Congress ratified the FARC peace accord, the guerrilla group’s membership journeyed from “temporary pre-grouping points” to 26 sites around the country. By February 18, 2017, all had arrived at 19 hamlet-sized “Hamlet Transition and Normalization Zones” (ZVTNs) and 7 encampment-sized “Temporary Normalization Zones (PTNs), and a six-month demobilization and disarmament process began. 6,804 FARC fighters registered themselves and gradually turned over their weapons to representatives of the UN mission at each of the demobilization sites.

Each ZVTN was guarded by a 1,200-person special police unit (Police Peace-Building Unit, UNIPEP) and military personnel maintaining a special security zone around the perimeter. No serious incidents took place within the zones’ perimeter during the demobilization phase. The Colombian government came under criticism, however, for the slow pace of the zones’ construction. By early March 2017, none was fully built, and half had barely begun their preliminary phase of construction; demobilizing guerrillas at several sites—including some pregnant or with children—were living under plastic sheeting with poor sanitation. By July 2017, nearly six months into the demobilization process, the UN reported that seven sites remained less than 75% built. In its defense, the government contended that the FARC had insisted—in part seeking to pull government services into rural zones—on demobilizing in sites so remote that transporting construction materials was difficult. The government ended up spending more than double its expected budget on the zones’ construction.

At least 2,256 guerrilla militia members—part-time participants in the FARC’s support network, who lived clandestinely among the population—also registered at the ZVTNs, where they were required to remain for a few days. A few thousand more guerrillas, amnestied for sedition or related crimes—though not for war crimes—were released from prisons. Many of them, along with other at-large guerrillas, await trial for serious war crimes in the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP), the post-accord transitional justice system.

During the demobilization process, the UN mission verified compliance with the ceasefire between the government and FARC. Any violations were investigated in a “tripartite” manner by teams made up of Colombian security forces, FARC members, and representatives of the UN mission, most of whom were Latin American military personnel. The mission documented only 10 “serious” ceasefire violations.

By August 15, 2017, the demobilization process was complete. The guerrillas turned in 8,994 weapons, more than 1.7 million pieces of ammunition, and tens of thousands of grenades and other explosives, while revealing the location of 1,027 weapons caches. By January 2020, a total of 13,185 former FARC members were accredited as demobilized. All were eligible for a monthly stipend of 90 percent of Colombia’s minimum wage (about US$215 per month) for two years, along with a package of education, training, help with productive projects, or similar support. (The stipend has been extended, and continues to be in effect for most.) 98 percent entered the government healthcare system.

As of August 15, 2017, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia ceased to exist. Its members were free to leave the ZVTNs, whose name was changed to Territorial Training and Reincorporation Spaces (ETCRs). More than half left the sites within months, seeking opportunities or reuniting with family elsewhere.

In late August and early September 2017, the FARC held its first party congress in Bogotá, where it controversially decided to keep the initials FARC, now calling itself the “Common Revolutionary Alternative Force.” The FARC party has had difficulty attracting voters. Its candidates barely reached 50,000 votes in March 2018 congressional elections. In October 2019 gubernatorial and mayoral elections, its candidates received 119,000 votes. In those local elections the FARC, and coalitions including FARC, endorsed 300 candidates, 67% of whom were not former combatants, according to the UN Verification Mission. Of these candidates, 12 were elected, 3 to mayor’s offices. 2 of the elected candidates were women.

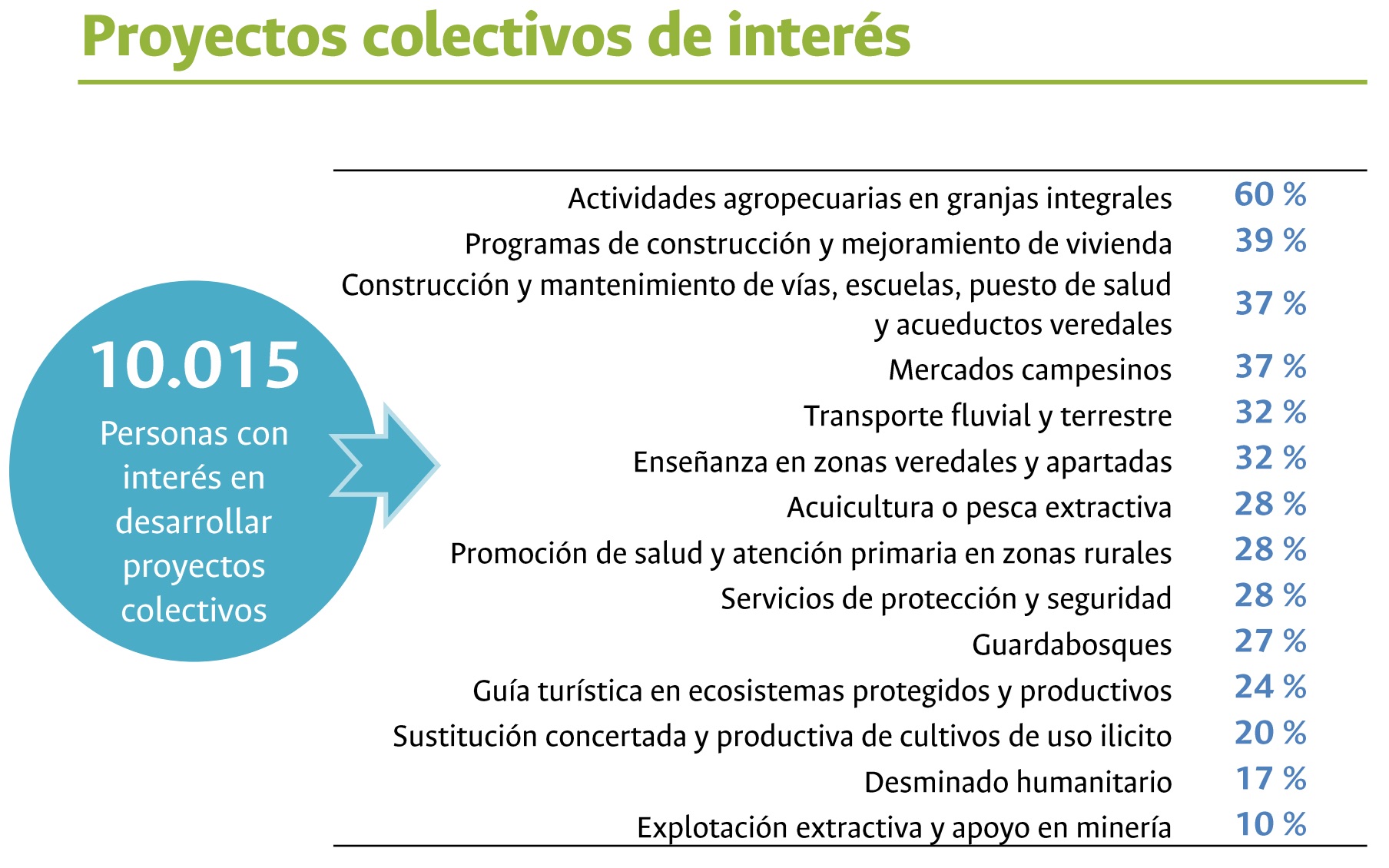

Both at the ETCRs and throughout the country, former FARC members began making the adjustment to civilian life. A June 2017 National University survey of more than 10,000 demobilizing guerrillas found that 23% were women, 81% were of rural or “urban-rural” (small town) origin, 54% were parents of children, 77% lacked a place to live, and a significant majority hoped to find work in farming or other rural pursuits. This posed a challenge, as the peace accord did not commit the government to furnishing land for ex-combatants who wished to farm.

Colombia’s Reincorporation and Naturalization Agency (ARN), which had run reintegration programs for thousands of individual FARC members who demobilized during the conflict, manages the government’s ex-combatant reintegration programs. Unlike past demobilizations, much of the FARC chose to demobilize collectively, as foreseen in the peace accord, remaining in the ETCRs or forming alternative sites in rural areas elsewhere. Many ex-guerrillas were suspicious of the ARN, regarding it as an adversarial “deserter” agency. The guerrillas set up a legal entity, Social Economies of the Common (ECOMUN), to manage productive projects for collective demobilizers. As the FARC remains on the U.S. government’s list of terrorist organizations, those who demobilize collectively, who continue to maintain a “FARC” identity, may not receive any U.S. assistance, whether through the ARN or otherwise.

As of March 2020, the UN Verification Mission reported, 1,225 individual and 49 collective productive economic projects had been approved for ex-combatants. The 49 collective projects benefit 2,156 former combatants, including 695 women. As of March 2020, 43 of those projects, benefiting 2,148 ex-combatants, had received funding. Their total cost is less than US$8 million (27.42 billion pesos), the Colombian presidency reported in February 2020. Of all the projects, about 70 percent were focused on rural development.

5,224 ex-combatants, 25% of them women, were enrolled in primary to high-school level educational programs, the UN Verification Mission reported in March 2020. Another 1,768 had “accessed vocational training through the National Training Service” (SENA), 29% of them women. 900 have been trained as bodyguards to protect threatened or high-profile former guerrillas; as of March 2020 767 former combatants, 146 of them women, were working as bodyguards within the Interior Ministry’s National Protection Unit.

Some guerrillas have broken from the FARC/Ecomun structure for reintegration, and begun pursuing their own separate productive projects. A key example is “Corporreconciliacion,” an effort led by former top FARC Southern Bloc leader Fabián Ramírez and Anayibe Rojas alias “Sonia,” which claims to represent 2,000 ex-guerrillas.

Others have reverted to violence, abandoning the reintegration process. While 13,104 FARC members formally demobilized, perhaps 800 rejected the peace accord entirely and refused to participate in the process. Of those who went through the demobilization process, the Fundación Paz y Reconciliación estimated that, as of late 2019, approximately 830 had taken up arms again. These approximately 1,600 former FARC members who remain in arms, the Fundación asserted in January 2020, operate within 23 FARC “dissident” groups active in 85 of Colombia’s 1,103 counties (municipalities). To these must be added an unclear number of new recruits with no guerrilla background: perhaps 600 to 800, which would make for a total dissident membership of about 2,400 fighters scattered across these 23 groups, each of which range in size from a few dozen to a few hundred members. The Fundación considers 11 of these groups to be part of the structure of Miguel Botache alias “Gentil Duarte,” a former FARC General Staff member and peace negotiator who rejected the final accord in 2016.

Though the 24 Territorial Training and Reincorporation Spaces (ETCRs) no longer exist as legal entities, and some have relocated, former guerrillas continue to be permitted to live there. Eleven may become permanent, ARN director Andrés Stapper said in August 2019. More than two-thirds are on rented land. Presidential Stabilization and Consolidation Advisor Emilio Archila said in January 2020 that each former ETCR continues to be guarded by a 100-person Army battalion. In total, Archila said in February 2020, the sites are protected by “the action of 2,500 members of the Army and 1,240 police.”

On February 26, 2020, Stabilization and Consolidation Advisor Emilio Archila said that 2,757 ex-combatants remain in the 24 former ETCRs. Another 1,200 people who were not combatants live in the former ETCRs; 900 are children. A March 18, 2020 statement from the ARN gave a figure of 2,893 ex-combatants living in the former ETCRs. As of March 2020, 9,412 former combatants were living outside the former ETCRs, according to the UN Verification Mission. In February 2020, the High Counselor for Stabilization and Consolidation gave a figure of 8,943 ex-combatants dispersed across 522 municipalities.

At the end of 2019, 9,720 ex-FARC members had cases before the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP), the post-conflict transitional justice system. This is out of a total of 12,235 defendants at that time. Ex-guerrillas are especially on the hook for the JEP’s Macro-Case 001, regarding kidnappings, and Macro-Case 007, regarding child recruitment, as well as cases covering geographic regions most battered by the conflict.

Protection of ex-combatants remains a big challenge. As of March 26, 2020, the UN Verification Mission reported, the total number of killings of ex-FARC members had reached 192, in addition to 13 disappearances and 39 attempted homicides. Of 185 killed as of early February 2020, a disproportionate share—79—were ex-guerrillas who had been released from prison, according to the FARC’s records. 16 were former guerrillas who had held some position of leadership in the group. The Prosecutor General’s Office’s Special Investigative Unit attributed responsibility in 93 cases: 36 to FARC dissident groups, 12 to the ELN, 9 to the Gulf Clan, 10 to small criminal groups, 6 to the EPL, and 13 to “individuals.” Other actors, among them security forces, have 1 alleged case each. As of December 31, 2019, 41 relatives of ex-combatants had also been killed.

The Presidential Counselor for Stabilization and Consolidation has pledged to continue assistance during the COVID-19 emergency to ex-combatants who remain in the former ETCRs. Technical assistance for productive projects, however, is restricted to telephone and e-mail. Outside visits to the former ETCRs, including from international aid agencies, have been suspended.